Anyone who has ever worked in retail has heard the term inventory. For businesses, inventory keeps customers happy and supply chains moving, ensuring that supply is available to meet demand.

Outside of a brick-and-mortar store, what is inventory? More importantly, how does inventory management keep commerce moving?

What Is Inventory?

Defining inventory can vary, based on your location in the supply chain. For producers, inventory is the raw materials that are required to produce goods that will be sold to intermediate or end consumers. Once they’re turned into commodities, these products are shipped to an intermediate consumer (like warehouses), retail outlet, or end consumer.

Intermediate consumers often store inventory for shipment to end consumers or fulfillment centers (like retail stores). These intermediate locations often rely on JIT inventory management to ensure that products are continually moving to their final destination, reducing liabilities and allowing commodities to turn a profit faster.

At retail locations, inventory is simply the quantity of any product on hand at any given time. The goal of the retailer is to sell the available inventory to multiple end consumers. The longer inventory stays on the shelf or “in the back”, it inherits storage costs, a higher risk of damage, and even obsolescence.

Types of Inventory

Three key types of inventory are used throughout the supply chain. Each describes the condition of the products throughout the inventory management process – and where it stands between production and delivery.

1. Raw Material Inventory

The raw material inventory is at the beginning of the supply chain. These are the materials the products will be created from. For example, steel and rubber are used to produce vehicles while textiles and wood are the raw material inventory used to produce furniture.

2. Inventory Management

As raw materials are used, they move to the next step in the inventory management process, designated as a work-in-progress. Anything identified as work-in-progress not only takes the cost of raw materials into consideration but also adds labor and overhead costs into the process. This concept allows companies to determine the necessary costs of producing any given item, then employ cost management strategies to reduce their cost per unit.

3. Finished Goods

At this stage in the inventory management process, finished goods are ready to be shipped to their next destination and sold to the consumer. From here, merchandise can either be sent to retailers or shipped directly to the consumer through online sales.

Inventory Examples

Depending on where they fall in the supply chain, examples of inventory can take many different shapes. At its most basic level, inventory is the physical count of the commodities at any point during the process.

Take an inventory example where a large manufacturer has products in various stages of production. To report their total inventory to stakeholders,the company will present it on its balance sheet as raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods. This informs their leadership as to where their inventory stands and what they are doing to maximize their resources.

In the retail world, inventory is a simple count of all items in stock, as well as their value. Taking regular inventory counts informs management of what is selling well, what isn’t, and what may be used to predict consumer or seasonal trends.

Why Taking Inventory Is Important

The physical process of taking inventory (or taking inventory stock) is the accounting for resources throughout the manufacturing process. Instead of simply counting the finished goods available, taking inventory counts raw materials, works-in-progress, and finished products.

Taking Inventory Example

Bike Company XYZ makes one type of bicycle. To produce it, it needs four materials: frames, suspensions, wheels, and tires. Their inventory process includes the materials in their possession (and their value), the number of works-in-progress (and their value), and the number of finished products on hand.

Each factor provides different business insights. Understanding the price of acquiring materials (plus labor) for works-in-progress helps a company determine their average cost of goods sold (COGS). And knowing how much finished inventory is available allows the company to set expectations for their sales partners, ultimately driving their sales to keep the supply chain moving.

What Is Inventory Management?

Regular accounting of raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods is just one aspect of inventory. Inventory management ensures that both ends of the supply chain are in harmony. That is, the company has enough raw materials on hand to produce goods while balancing the number of finished products ready to be sold later.

Through the process of inventory management, procurement and supply ensure that a company has enough raw materials to create its products. They also make certain the inventory is stored to minimize the risk of theft or damage, and there is a sufficient number of finished goods to avoid a backlog.

Inventory Management Examples

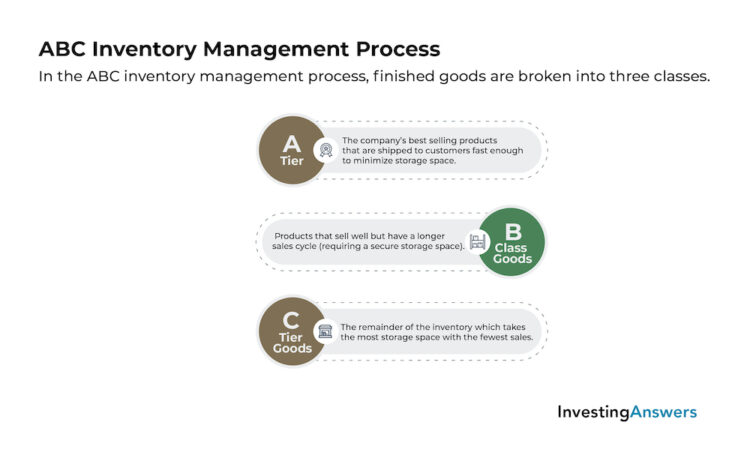

Two of the most common inventory management models are the ABC inventory classification model and the economic order quantity model (EOQ). Both take a different approach in ensuring that companies have enough inventory to manufacture goods and prepare them for sale.

EOQ Inventory Management

Using the economic order quantity (EOQ) inventory management process, managers balance the cost of having item surpluses and then storing this inventory with the cost of a “stockout” or shortage of an item. This balance should minimize storage costs while reducing the chance of production overruns. Analysts will determine which products sell best, then measure their order and carry costs to determine peak performance.

Why Inventory Management Is Essential in Business

Although inventory management is a critical business procedure to control costs and meet consumer demand, it has many more implications for business operations, especially when it comes to understanding business health and keeping the supply chain moving appropriately.

Taking Advantage of Inventory Turnover

Inventory management also helps businesses understand their inventory turnover (how fast a company can replenish its inventory). By maximizing turnover, a company can reduce its storage costs and ensure that it produces what customers want to purchase. This directly affects profits and assets on hand which has implications for tax liabilities at the end of a company’s fiscal year.

Limiting Ancillary Costs

If a company has too many raw materials, it may be forced to pay for additional warehousing, security, and transportation. If a company has too many finished goods, it has to store them and protect them from warehouse damage. Good inventory management practices ensure that companies produce the right products and continue the supply chain moving from factory to end consumer – not being required to keep them stored at warehouses.

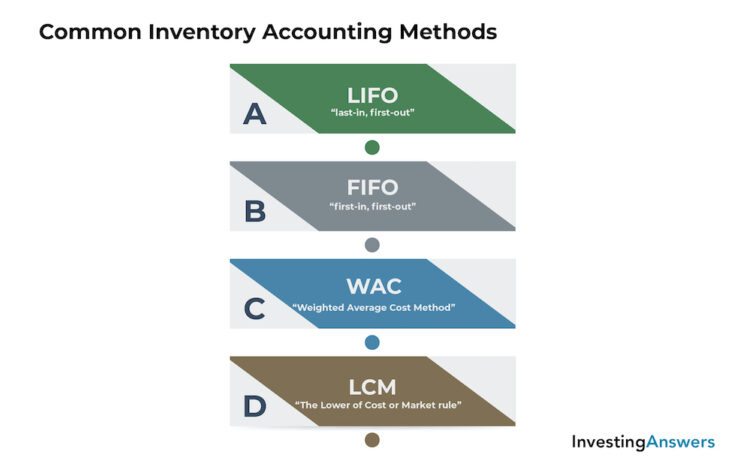

Common Inventory Accounting Methods

Based on business practices and financial goals, there are three primary inventory accounting methods companies use to value their raw materials:

- Last-In, First-Out (LIFO)

- First-In, First-Out (FIFO), and the

- Weighted Average Cost

LIFO

The “last-in, first-out” (LIFO) inventory accounting method assumes that the most recent units to come in are the first to be sold, regardless of their cost. Companies tend to use the newest and most expensive materials to create finished goods. Therefore, businesses that tend to hold onto inventory over longer periods of time should benefit from LIFO inventory accounting because it reduces their reported net income. In turn, this can minimize the tax liability on their inventory reserve.

FIFO

Contrary to LIFO inventory accounting, the first-in, first-out method assumes that all items are sold in the order they are acquired, regardless of the cost. If a company produces 50 units at one price and then 70 at a higher price (and sells 50 units), it would expense the cost of the first 50 units (as cost of goods sold).

Companies who utilize FIFO for their inventory accounting often try to gain savings by managing higher costs of first-in inventory.

WAC

Under the weighted average cost method (WAC), inventory managers use a simple formula to average the cost of goods available for sale over the number of units available.

Under a periodic inventory system (which is the most common among businesses), the cost of goods sold is determined by counting the ending inventory and their cost, which then plays into the weighted average cost. But when applied to a perpetual inventory system, the regular count provides a continual count of inventory and COGS, which then creates a “moving” average cost.

LCM

The “lower of cost or market” rule (LCM) is not an inventory management process, but rather a rule that determines which method should be used to report inventory value. Because goods and commodities can shift price over time, companies report their inventory at its actual cost or its current market value, whichever is lower. That way, if inventory is obsolete or its value has diminished, its reported value won’t be exaggerated.

LCM inventory accounting minimizes the cost of a product and is either based on the cost to produce or acquire it (historic cost) or the price of selling it to the customer (market value). In instances when a product could have a negative net realizable value (NRV), this method allows companies to record the inventory as a loss, thus reducing their liabilities.

What Is Inventory’s Primary Business Driver?

For businesses that produce finished goods, the primary driver of inventory is consumer demand. If their production is aligned with the law of supply, it will continually derive increased profits from customers. By optimizing for demand, businesses can create enough products to fulfill market needs without maintaining excessive storage or security costs.

Conversely, companies can also face inventory drivers that negatively affect their business. If a product is no longer in demand – or if the work-in-progress time falls out of alignment with market cycles – the amount of inventory held can hurt a company’s bottom line. In an ideal world, a company will produce enough finished goods to align with consumer demand, which ultimately acts as a business driver.