What Is a Bond?

A bond is an agreement between an investor and the company, government, or government agency that issues the bond. When investors buy a bond, they are loaning money to the issuer in exchange for interest and the return of principal at maturity. Because bonds traditionally pay the investor a fixed interest rate periodically, they are also known as fixed-income securities.

Unlike stocks, bonds don’t make the investor an owner of the bond issuer: the investor becomes a lender to a company, city, or government.

Who Are Bondholders?

Bondholders are investors who own bonds and are considered creditors to the issuing organization. Bondholders can either decide to sell their bonds to other investors or receive interest payments by holding the bonds (interest payments are typically received semi-annually).

How Do Bonds work?

When an investor purchases a bond, they are 'loaning' that money (the initial amount is called the principal) to the bond issuer, who is usually raising money for a project.

Let’s say a new company is ready to expand but doesn’t have enough funds for expansion. They may turn to the public for their financing needs. One way to gain more capital is by issuing bonds.

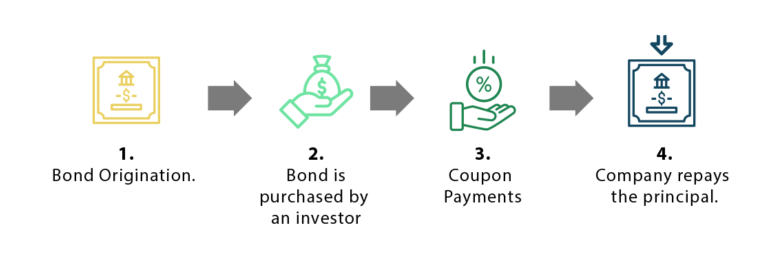

The Lifecycle of a Bond

The company issues a bond, also known as bond origination.

The bond can then be purchased by an investor. That investor is loaning money to a company for a specified period of time.

The investor receives regular interest payments from the issuer until the date of maturity. These periodic interest payments are called “coupon payments.” The amount of the coupon payments is determined by the coupon rate, which is expressed as a percentage of the principal.

When a bond matures, the issuer (i.e. company) repays the principal to the investor.

Alternatively, investors can sell their bonds before the bond matures.

Bond Example: How It Works

Let’s look at an example of how a bond works:

Company XYZ issues a 10-year bond with a face value of $10,000 and a coupon rate of 5%.

The investor agrees to buy that bond under the conditions that the company will pay $500 each year (in interest) over a 10-year period.

At the end of those 10 years, the company will repay the investor $10,000.

Bonds vs. Stocks

When a company needs financing, it has the option of using stocks or bonds. A company can go public and make an initial public offering (IPO), selling shares of its company. When someone buys these shares (stock), they are then the legal owner of a portion of that company. In this case, the company has used equity financing.

With a bond, the investor does not receive equity in the company. The company borrows from the investor, and the investor receives the interest payments and principal of a bond, regardless of how high or low the company’s stock price becomes. In this case, the company has used debt financing.

How to Invest in Bonds

Stocks are traded publicly on a large, centralized exchange such as NASDAQ or the NYSE. Conversely, bonds are typically sold over the counter (OTC).

Investors must buy bonds from brokers who can better help them understand associated fees and commissions. In the case of Treasuries, investors may buy them directly from the US government’s website, Treasury Direct. Brokerages such as Vanguard and Fidelity also offer brokerage accounts where investors can invest in Treasuries.

How Are Bonds Rated?

It’s important to know the associated risk of purchasing a bond. The bond rating describes an organization’s likelihood of defaulting and not paying its bondholders.

A bond’s rating is a score given by three primary bond rating agencies:

These agencies rate bonds using a system that combines letters, numbers, and symbols. Below is an example:

Standard & Poor's Bond Rating System

| Rating | Description |

| AAA | Highest rated and offers the lowest risk. |

| AA | Generally low risk and unlikely to default. |

| A | May be affected by changes in the economy or during times of hardship. The obligor’s ability to meet financial commitments is still strong. |

| BBB | More susceptible to economic downturns and adverse conditions. |

| BB | Significant speculative characteristics and a fair amount of uncertainty. |

| B | The issuing organization for these bonds still has the means to pay back its bondholders, but adverse conditions can affect their ability to pay even more than BB-rated bonds. |

| CCC | Risk is dependent on the organization having favorable financial circumstances and upon the obligor’s ability to meet financial commitments. |

| CC | One of the lowest-rated bonds, these are considered “junk bonds.” |

| D | Lowest rating that’s issued when the issuing organization has already defaulted. |

If you have a low risk tolerance, you’ll likely choose to invest in bonds with a higher (safer) rating. If you have a high-risk tolerance, you may consider investing in bonds with a lower rating.

How Bonds Are Priced

A bond’s price equals the present value of its expected future cash flows.

Bond Pricing Example

Say you purchase a bond for $1,000 (present value). The bond has a par value of $1,000, a coupon rate of 5%, and 10 years to maturity. The bond will return 5% ($50) per year. At the maturity date, you will be paid back the $1,000 par value. That means the total expected future cash flow of your bond is $1500.

If new bonds are issued with interest rates of 7%, your bond will return less than newly issued bonds (your coupon of 5% is less than the new rates of 7%). These new bonds will be more attractive to investors and demand for them will increase, causing older bonds’ prices to fall: your bond value drops, but your expected future cash flow does not change.

Bond values have an inverse relationship with interest rates: When interest rates increase, bond prices decrease (and vice-versa).

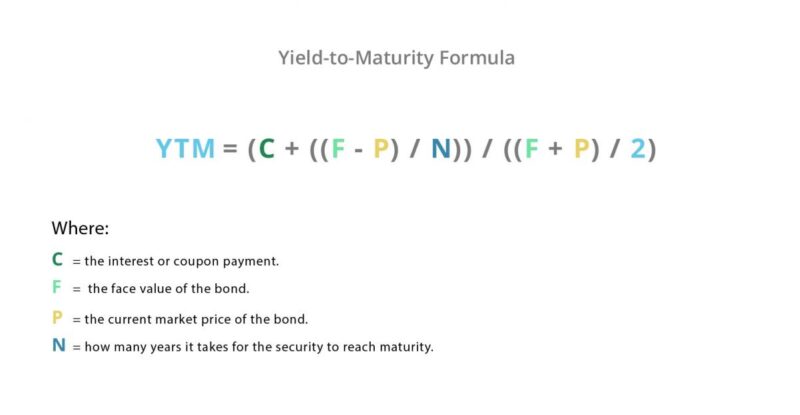

The Yield-to-Maturity Formula

If a bond is held until maturity, the bondholder’s return is called the Yield to Maturity (YTM).

The YTM Formula can be calculated as follows:

the interest or coupon payment.

the face value of the bond.

the current market price of the bond.

how many years it takes for the security to reach maturity.

You can use a financial calculator or an online Yield to Maturity (YTM) Calculator to calculate your results.

Example of Yield-to-Maturity

Suppose that the market price of a bond is $950 and the face value is $1,000. The annual coupon rate is 7% with yearly coupons. The number of years to maturity is 10 years. Using a financial calculator or spreadsheet, we can calculate the YTM to be 7.7363%.

If you buy this bond today and hold it until maturity, you should earn 7.74% per year.

Typical Bond Rates

According to investment researcher Morningstar, long-term government bonds have returned between 5% and 6% since 1926. Domestic bonds, according to the Barclays Aggregate U.S. Bond Index, have returned an average of 4.62% from 2004 to 2014.

When compared to the S&P 500 – which returned an average annual total of 8.11% within the same 10-year period – bonds have returned significantly less (but offer less risk and volatility).

What Factors Affect Bond Rates?

There are two major factors that can affect the rates of bonds:

Finances of the Issuing Company

Generally, corporations with better creditworthiness are able to offer lower interest rates because they’re less risky. To attract potential investors, less financially-secure companies may have to offer higher interest rates.

Inflation Rates

When inflation rates increase, bond prices tend to decrease. This is because inflation is an advantage to borrowers, but a disadvantage for lenders (like bondholders). So, bonds are less attractive and prices drop. One way that long-term bonds account for expected increases in inflation rates is to offer higher interest rates.

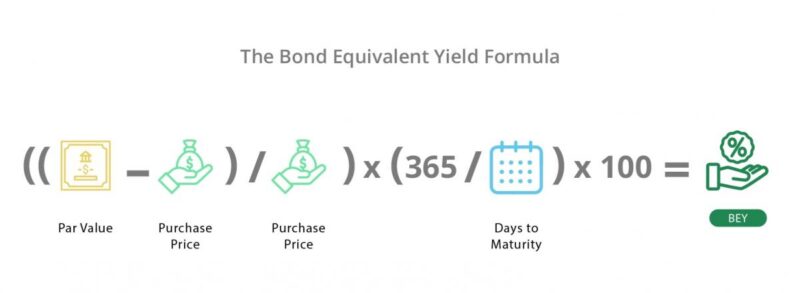

What Is the Bond Equivalent Yield?

The Bond Equivalent Yield (BEY) is a formula that allows investors to calculate the annual yield on a discount bond.

When a bond is traded at a lower price than its face value (or par value), it is a discounted bond. Discounted bonds are sold when interest rates increase and are greater than the coupon rate offered by the bond.

Calculating the BEY is helpful if you want to compare your long-term bond with a short-term investment.

Bond Equivalent Yield Formula

BEY can be calculated by first taking the par value (face value) and subtracting the amount paid for the discount bond. Dividing that number by the purchase price again, you’ll get the first number needed for the calculation.

The next step is to divide 365 by the number of days until the bond maturity date. This will be your second number needed for the calculation.

Multiply the first number with the second number, then multiply 100 for a percentage:

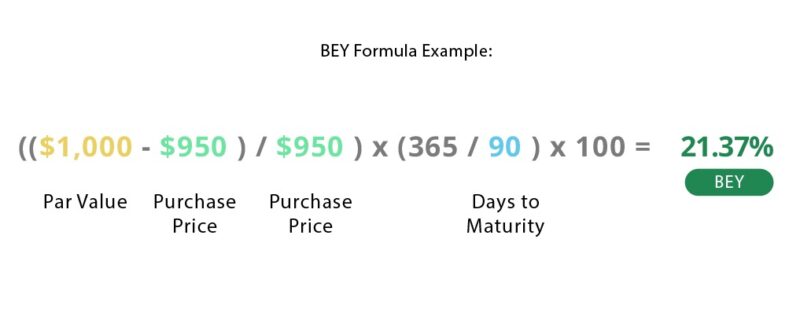

BEY Formula Example

Let’s say you bought a bond for $950 with a face value of $1,000. It takes 90 days to reach maturity. Using the BEY formula:

The final bond equivalent yield is 21.37%.

Four Main Types of Financial Bonds

Different categories of bonds offer investors a variety of choices. There are four major bond types in the US markets, each representing four major categories of issuers.

Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds (or “muni” bonds) are debt obligations issued by local or state agencies. These types of bonds are a way to raise money for infrastructure projects like the construction of a convention center, water treatment facility, or regional airport. Generally, these bonds are not subject to federal income taxes. In some cases, the bonds may not be taxable to residents of the state they are issued in.

There are two main types of municipal bonds:

General Obligation (GO) Bonds

A general obligation bond is typically used to fund projects that benefit the public community as a whole. This type of muni bond is secured by an issuing government's pledge to use all available resources. These resources may even be tax revenues. This is then used to repay bondholders. Each state has specific laws for how many GO bonds can be created and how they will be used.

Revenue Bonds

Unlike GO bonds, revenue bonds must fund projects that will provide a revenue source. This could be a stadium or toll bridge. The revenue bond relies on this one project to repay bondholders, while GO bonds repay bondholders with multiple revenue streams within the municipality. This makes the revenue bonds a higher risk than GO bonds.

Government Bonds

Government bonds (also known as Treasuries or sovereign bonds) are bonds issued by a national government to raise money and support government spending. Government bonds are typically low-risk investments because they are backed by the issuing government and therefore have lower default risk than other types of bonds.

In the US, there are three categories of government bonds, which differ by par value and maturity:

Treasury Bills

Treasury bills are short-term debts that expire in less than one year. They are offered in various denominations as low as $1,000.

Treasury Notes

Treasury notes mature in two, three, five, or ten years and usually have $1,000 face values (although some can have $5,000 values).

Treasury Bonds

Treasury bonds are long-term bonds issued by the U.S. treasury. Their maturity ranges anywhere from 10 to 30 years.

Corporate Bonds

When investors buy corporate bonds, they lend money to a company to be used for a variety of reasons (e.g. buying more products, financing mergers and acquisitions, refinancing debt, expansion).

Corporate bonds are not usually sold directly through the issuing company itself but through corporate trustees. Using a third party helps to alleviate certain risks, offer valuable knowledge to investors, and help communicate with corporations.

Buying corporate bonds carries some risk, however, since the company can fail to pay periodic interest payments or the principal amount once the bond fully matures. If this happens, the company will default on its bond.

Investors must consider the credit quality of a company and understand the issuing company’s default risk. Companies with better creditworthiness can issue more debt at lower rates.

There are common rankings of corporate bonds:

Senior Bonds

In the event that the company goes out of business, senior bonds allow bondholders to claim a company’s assets first.

Senior Secured Bonds

Senior secured bonds are backed by the issuing company’s property or assets. They are ahead of other lenders when it comes time to be repaid.

Senior Unsecured Bonds

Unlike senior secured bonds, senior unsecured bonds are not backed by the company’s property or assets. However, bondholders still rank higher than other unsecured bondholders in the repayment queue.

Subordinated Bonds

Subordinated bonds receive their payments before other shareholders and creditors (but still have less priority than the types of corporate bonds listed above).

Convertible Bonds

A convertible bond gives the bondholder the ability to turn the bond into common stock. Each bond can be turned into a predetermined number of shares. The conversion can be done at certain periods in the bond’s life, and the bondholder can decide if they want to carry out the conversion or not.

Agency Bonds

Agency bonds are issued by government agencies to finance public-relations projects such as agriculture reforms and loans to home buyers. The yields on agency bonds are typically higher than on Treasuries but lower than for corporate bonds.

There are two types of agency bond entities:

Government-Sponsored Enterprise

A government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) is a privately-held entity established by Congress. One example is the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae).

Federal Agencies

A federal agency, such as the Department of Agriculture or Department of Homeland Security can issue agency bonds. This includes the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae).

Bonds vs. Loans

One of the biggest advantages to holding bonds is that – unlike loans – they are highly tradeable. Bonds can be traded in the market before reaching maturity, making them liquid assets.

There are some other notable differences between bonds and loans:

Source

Organizations and companies issue debt securities that are bought by many investors (bonds). Loans, on the other hand, are usually issued to companies by a single lender (such as a bank.)

Interest Rates

Because of bonds’ liquidity, bonds are generally lower risk for investors than loans are, and therefore offer lower yields. Loans tend to have higher interest rates.

Companies can benefit from bonds’ fixed interest rates. For example, some long-term bonds come with a locked interest rate of 10 years or more. Long-term loans, however, are subject to interest rates that can significantly increase over time.

Type of Interest Rate

Both bonds and loans can have either fixed or variable rates.

Ownership

Bonds are usually issued by governments, organizations, or corporations. Loans are borrowed by corporations or individuals.

Some companies choose to issue bonds over loans because they come with fewer restrictions. For example, some banks may want a company to completely pay off the loan until any further acquisitions are made. With a bond, companies have more financial flexibility and fewer restrictions on their decision making.

It is much easier for a company to obtain a loan than to issue a bond. For companies to issue bonds, they must comply with SEC requirements, a process that generally has higher transaction (legal and marketing) costs than obtaining a loan.

Furthermore, loans offer more flexibility in terms of refinancing. Loans can change along with the company’s financial fluctuations, unlike bonds,which are often more restricted.

Bond Glossary

If you'd like to read more in-depth bond-related definitions, check out these definitions:

Collateralized Bond Obligation - A bond that uses high-yielding junk bonds as collateral.

Commercial Paper - A short-term commercial bond that matures in less than three months.

Convertible Bond - A bond that can be exchanged for other investment securities.

Covenant - The specific promises the bond issuer sets in the contract.

Credit Rating - A grade assigned to a bond to indicate how risky it is.

Debentures - An unsecured bond not backed by collateral.

Maturity Date - The specified date when the bond issuer must pay back the investor's principal.

Municipal Bond - A bond issued by a state or local government.

Treasury Bond - Long-term bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury.

Discover more bond-related definitions on the InvestingAnswers Bond Category Page.