There are things in life we all wish we'd never heard of: bacon-flavored toothpaste, tramp stamps, combovers, meat from a can.

That sentiment is true in the investing world, too, especially for those of us who have been burned once or twice.

But remember, information is the best asset, and knowing more is always better than knowing less. Ask yourself how many kinds of bonds you can name, and you'll know what I'm talking about.

Here are a few more that you've probably never heard of.

A step-up bond has a coupon that increases ('steps up'), usually at regular intervals, while the bond is outstanding. Government agencies, as well as Fannie Mae and Sallie Mae, issue these bonds.

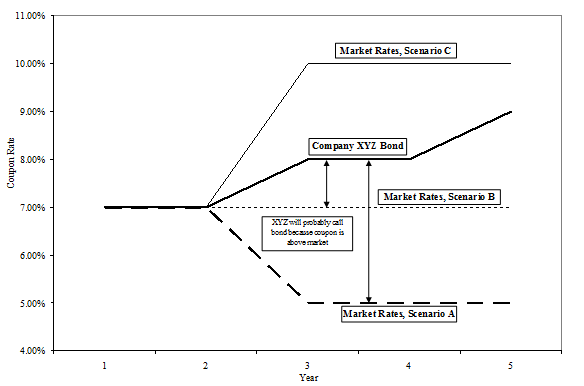

Consider a five-year step-up bond issued by Company XYZ. The coupon rate might be 7% for the first two years, increasing to 8% for years three and four, and 9% in the fifth year. Note that the initial coupon rate on a step-up bond is usually above market.

Many step-up bonds are callable, which gives issuers some protection against falling interest rates. So if after three years the bond is paying 8% but market rates are down to 5% (Scenario A, as pictured in the chart below), Company XYZ would be paying a relatively high interest rate on its debt. It would probably call the bonds and reissue the debt at a lower rate.

In fact, if rates simply stay the same (Scenario B), Company XYZ will probably call the bond. Conversely, if market rates rise to 10% (Scenario C) and Company XYZ gets to pay only 8% for its debt, well, then it's getting a deal.

There are several advantages to step-up bonds: They offer coupon payments that somewhat offset inflation, they usually come from high-quality issuers, and they are fairly liquid. Another advantage is that they lessen the interest-rate risk for the investor: The increasing rates provide a better yield than a fixed-rate note (as long as the bond is not called).

If rates rise, for example, the prices of step-up bonds don't fall as much as a similar noncallable bond. (This is because of the future increase in coupon rate.) If rates fall, the price of a similar noncallable bond tends to increase more than the step-up's price.

Payment-In-Kind (PIK) Bond

A payment-in-kind bond (PIK bond) gives the issuer the option of making interest and principal payments with either cash or additional bonds. One of the most famous PIK bond issues came in 1989 when RJR Nabisco issued $1 billion of them as part of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts' well-known leveraged buyout of the company.

Take a $1,000 face-value Company XYZ PIK bond with a 12% coupon. If this were a traditional bond, you'd receive a $60 cash interest payment every six months. ([$1,000 face value x 12% coupon rate] / 2 = $60) But because it's a PIK bond, you might get some interest paid out in cash and the rest in more Company XYZ PIK bonds. (For example, using the above example, you might receive $10 in cash and $50 in Company XYZ stock every six months. (Note that the par value is equal to the interest payment.)

The amount of the coupon payment that may be made 'in kind' -- that is, with more bonds -- usually changes throughout the life of the bond, according to a schedule set forth in the indenture agreement. Often, most of the coupon is paid in kind early on, with a larger cash payment later (presumably as the company sees the financial rewards of its use of the bond proceeds). In some cases, PIK bonds have variable-rate coupons. Note though, that in general, even though you don't get cash interest payments, accrued interest is still taxable.

Ultimately, PIK bond issuers can issue debt forever because whenever interest or principal is due, they just make those payments with more bonds. Theoretically, this makes default less likely, but many financial professionals agree that it really just delays the issuer's inevitable demise.

A baby bond has a par value below $1,000. However, the term also refers to savings bonds issued by the Treasury Department from 1935 to 1941. In the United Kingdom, the term refers to a tax-exempt savings program for children.

Baby bonds usually carry the same terms, coupon and maturity as traditional bonds, although many are zero-coupon bonds. Let's assume Company XYZ wants to issue $5 million of bonds with a 6% coupon. Company XYZ may not see much interest from the capital markets for such a relatively small issue, because at $1,000 face value per bond, Company XYZ would only issue 5,000 bonds.

However, if Company XYZ issued $5 million of baby bonds with a $250 face value, it may actually generate more demand for the issue for two reasons -- the bonds are more affordable to small investors, and the market for the bonds would be more liquid because there would be 20,000 bonds outstanding ($5,000,000 / $250) rather than 5,000 at the $1,000 face value. The bonds would still carry a 6% coupon, and Company XYZ's principal and interest payments would remain the same.

The Investing Answer: Though the bond world seems to revolve around Treasurys and corporate bonds, there's a whole lot more to it than that. Don't let ignorance shut you out of potentially great investments -- go out there and learn more! The three bonds we've shown you are unusual, but they could be just the thing you're looking for.