PC maker Dell (Nasdaq: DELL) kickstarted the era of affordable personal computers -- and made many people very wealthy along the way.

Its rise was meteoric. Its stock price shot from about $1 in early 1998 to more than $50 in early 2000. But the company would never again have it so good.

Then, it lost its way, eventually culminating in its recently proposed buyout.

It's hard to pinpoint precisely where Dell got off track, but it's clear that the company became an also-ran in the various technology niches in which it operated. It's a business badly in need of a fix.

And Dell's board apparently realized that it's much easier to fix this business away from the scrutiny that comes with being a public company. So Dell is attempting to 'go private' in a $24 billion deal that will enable founder Michael Dell and his investment partners to make radical moves that may hurt the company's results on a short-term basis -- which the public never likes to see -- but (presumably) set the stage for long-term growth.

It's a big deal when a company as prominent as Dell goes private, but it's hardly unheard-of. And every time it happens, there are things you can learn to become a smarter investor.

Let me explain…

1. Not All Revenue Is Created Equal.

The last five years proved to be especially challenging for Dell. Although Dell made a number of acquisitions, its sales in fiscal (February) 2012 of $62 billion were just 1% higher than four years earlier.

Translation: Without the revenues that those acquisitions brought in, Dell's sales base actually would have shrunk by a considerable amount in recent years.

Meanwhile, other high-tech companies such as Google (Nasdaq: GOOG), Apple (Nasdaq: AAPL), Amazon.com (Nasdaq: AMZN) and Microsoft (Nasdsq: MSFT) managed to maintain more respectable growth rates.

That's an important lesson for investors. It's not enough for a company just to increase its revenues. The way in which the revenue increases is just as important.

2. Strong Companies Get Bought Out, Too.

Fixing a broken business is one of the two main causes behind companies' decisions to exit the public markets. The other cause: when a company is doing quite well, controls an attractive industry niche and would aid an even larger firm in its efforts to crack a new market. That's the method deployed by GE (NYSE: GE), which identifies industries that it hopes to dominate and then finds the best operators in that industry. Right now, GE is snapping up a number of great companies to help form the backbone of a new division, GE Energy.

3. Buyouts Can Be Great For Shareholders.

Although it may seem that Dell's suggested $24 billion purchase price was the result of a concrete analysis of the company's value, buyouts are actually more art than science. Both parties start off with very different views of what a business is worth. And then they parry and thrust until a mutually satisfactory number is arrived upon.

There is one hard and firm rule that these negotiators must heed. Any buyout price must be considerably above the current trading price. Otherwise existing shareholders would wonder if a buyout gives them any benefit. When Dell's buyout talks began in the summer and fall of 2012, shares traded below $10. So the $13.50-per-share offer to take the company private represents nearly a 40% premium. With such a built-in booster shoot, most shareholders are likely to give a thumbs-up to the transaction.

[InvestingAnswers Feature: How to Play the Buyout Game: 3 Tips For Finding the Best Deals]

4. Shareholders Have Choices When Buyouts Happen.

When a company receives overtures from a potentially interested buyer, the company's board of directors must assess the sincerity of the interest and determine what price the buyer is hoping to pay and whether the deal will be paid for in cash and stock. The board must then make its own assessment of the company's value, generating what is known as a 'fairness opinion' (which is often provided by investment banks that act as an advisor in any transactions).

To be sure, not all corporate boards act in the independent manner that they should. Many times, the board members will be close friends with top management and are inclined to simply 'rubberstamp' whatever management wants. Whenever that happens, outside shareholders can raise an objection. You'll often see a mutual fund or hedge fund manager seek out alliances with other outside shareholders to force management and the board to reject a buyout offer until its value has been increased.

Assuming a buyout will proceed as planned, investors can either sell their shares now or wait for the transaction to close. Often times, the current share price will be a bit below the buyout price, reflecting the possibility that the deal will fall through. That's why many investors choose to hold on until shares move up to the buyout price. If you do nothing, the cash from the sold shares will simply be deposited into your brokerage account when the deal closes -- typically three to four months later. (Unless a company is being acquired with another company's stock, in which case you'll receive stock of the acquiring company instead.)

If you don't want to sell, there isn't much you can do to block a deal, unless larger investors (such as hedge funds and mutual funds) are against the deal and actively reach out to enough investors to gain control of more than 50% of the company's voting stock. This is a fairly rare occurrence.

5. It's Smart To Be Wary Of Buyout Rumors.

Dell is not the first technology company to be acquired or go private. The entire industry is always in the midst of rapid change, with new products that can leapfrog existing products. Many investors start to focus on companies like Dell when they have stumbled badly, presuming that management will fix the business -- or sell it.

By the time shares of Dell traded below $10 a share last summer, the company's market value had slumped to $16.5 billion of just 25% of its prior year sales base. That's virtually unheard-of and a clear sign that some sort of bold move might soon take place.

There's an old saying on Wall Street: Never buy a company's stock in hopes of a buyout. Indeed, most rumored buyouts never even come to pass. Instead, look at the possibility of a buyout as just one of many potential positives when you are assessing a beaten-down stock.

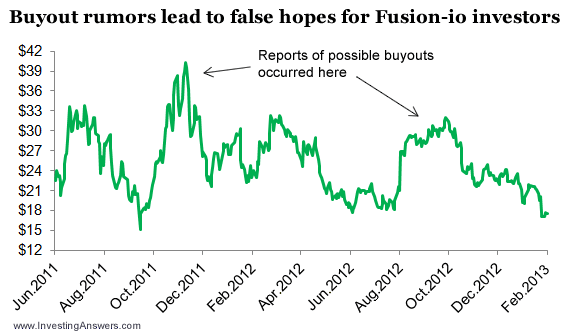

Let's use data storage firm Fusion-io (NYSE: FIO) as an example. This company has been repeatedly mentioned as a potential buyout target, and every time the rumor mill churns up, the stock spikes nicely higher. And then the rumors fade and those who had been hoping for a buyout are left holding the bag.

Now, with shares trading below $18, Fusion-io is trading closer to the fundamental value of its business. Some analysts think this company has a very bright future, and some even suggest that a buyout will eventually happen. Making a bet on such an outcome looks much wiser when shares are washed out, as they are now.

The Investing Answer: There's a good chance that some of the stocks in your portfolio will be bought out in coming years. It's the natural Darwinian evolution of publicly traded companies. Indeed, many of the companies that were in the original Dow Jones Industrial Average don't even exist as public companies any more. They've long since been acquired.

To reiterate, never buy a stock simply because you think it has buyout potential. But use that sentiment as part of your broader investment thesis for a stock.