On a sunny morning, 70 middle school students hop off the school bus and cram themselves into a classroom originally meant to seat 20 kids. Taking notes while trying to avoid your neighbors' elbows is hard, but the hardships these students face are nothing compared to the ones challenging the thousands of state workers recently laid off.

If you're a resident of one of the most troubled states in America, here's a glimpse of what's to come: higher taxes, layoffs of state workers, longer waits for public services, more crowded classrooms, shorter school years, higher college tuition and less support for the poor and the unemployed.But for those of you living in places that aren't in such rough shape, don't get too comfortable. Think about this: The 10 states in the worst financial condition account for more than one-third of America's population and economic output.

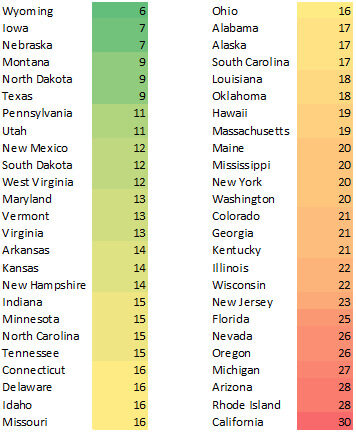

The Pew Center on the States, a nonpartisan think-tank based in Washington D.C., recently used California as the poster child for fiscal dysfunctionality. The Pew Center identified the six factors most responsible for California's ongoing fiscal woes and then scored the other 49 states on how similar they are to the beleaguered Golden State.

The six factors are (1) high foreclosure rates; (2) increasing joblessness; (3) loss of state revenues; (4) relative size of budget gaps; (5) legal obstacles to balanced budgets -- specifically, a supermajority requirement for some or all tax increases or budget bills; and (6) poor money-management practices. The results are in the table below, with California being assigned the benchmark number of 30.

The immediate problem, and the one dysfunctional states like California, Rhode Island, Arizona, Michigan, Oregon, Nevada, Florida, New Jersey, Wisconsin and Illinois, are dealing with, is the requirement that they balance the budget every year. States are forbidden from running deficits. That doesn't mean they can't borrow money to fill the holes. It just means that for every dollar that goes out, whether to debt payments, pension obligations, education, welfare or Medicaid, there must be a corresponding dollar coming in.

But if all states have to balance budgets, why are some in such terrible shape?

Simply put, the states in the most trouble have put off difficult decisions for decades. They have not been willing to finance expenditures with tax dollars. They did not put aside money in 'rainy day funds' like many of their healthier neighbors. Instead, they kicked the can down the road by borrowing money, making accounting adjustments, and making promises to change things in 'the future.' Add one recession to the recipe and you end up with a handful of states that may be past the point of no return.

State governments can plug holes by borrowing, selling assets, reducing expenses, increasing revenues or, if they're feeling creative, using accounting tricks or asset grabs.

They can also just ignore the problem altogether by refusing to pay their bills, a strategy that Illinois has been using all year.

Because the state government refuses to either raise taxes or cut spending, Illinois simply stopped paying the roughly $4.7 billion in unsecured payables it owed to public schools, rehabilitation centers, child care providers, the University of Illinois and other unsecured creditors as of the beginning of July. The University of Illinois has been stiffed on 45% of its state appropriation this year and legislators helpfully suggested that the university borrow the money and wait for the state to pay them back.

Arizona went the asset-sale route. It sold the buildings that house its Senate and House of Representatives as well as the State Capitol Executive Tower. The deal allows the state to use $735 million in sales proceeds to fill its budget gap and in return it will pay rent to its new landlords for 20 years.

In 2009, Hawaii cut expenses by going to a four-day school week, a move that more and more states are exploring. As of now, there is little official data on the performance of students in 4-day versus 5-day school districts, but many superintendents have used anecdotal evidence to illustrate negative impacts on students with a shorter school week.

Other states are just desperately trying to grab whatever is available. To fund the state's university system, Colorado is trying to get its hands on a $500 million surplus from Pinnacol Assurance, a state workers' compensation insurer that was privatized in 2002. Many other states have used the still theoretical federal health care dollars to balance their budgets. These are dollars that Congress has not even appropriated yet, but have already been 'spent.'

Even with all the acute crises that have developed, the bond market has largely shrugged off concern for state governments. Because states cannot declare bankruptcy, they cannot discharge or restructure debt. Investors believe that if any state got into real trouble, the federal government would intervene. And most experts agree the federal government would have little choice but to help out any state that defaulted on legal obligations to bondholders or pensioners.

States, too, have put structures in place to build investor confidence. In New York, a trustee intercepts tax revenues and makes some bond payments right off the bat, before politicians can get their hands on the money. California has a 'continuous appropriation' for debt payments, so bondholders know they'll get paid regardless of whether the rest of the budget is approved.

But even in a best-case scenario in which states muddle through the most acute phases of this crisis and come out intact, these budgetary problems are not merely recession-related problems. The states, and indeed the federal government, are dealing with long-term challenges that will eventually require action.

Take pensions, for example. Pensions are just another form of debt. They are an obligation that must be paid out year after year. States don't have to disclose how much they owe retirees, and I'll give you one guess why state officials across the board refuse to value their pensions at market rates -- the results are horrifying.

As described in the New York Times series, Payback Time, Joshua Rauh, an economist at Northwestern University, and Robert Novy-Marx of the University of Chicago, recently recalculated the value of all 50 states' pension obligations the way the bond markets value debt. They put the total obligation at $5.17 trillion, though only $1.94 trillion has been set aside in state pension funds. The $3.23 trillion gap is more than three times the amount the states owe bondholders.

'When you see that, you recognize that states are in trouble even more than we recognize,' Rauh said.

And regardless of whether the states have enough money in their pension funds, they are legally bound to pay retirees' benefits. Once pension funds are out of money, the benefits have to be paid out of general revenue. In Illinois' case, pension obligations would eat up about half the state's cash every year. Since this would more or less bring state operations to a halt, any state caught in this predicament would likely head to D.C. for assistance.

After all this, it's not difficult to imagine a future in which a higher and higher percentage of tax revenue goes toward benefits for retirees and interest on debt payments, leaving less and less for those things that receive a lot of lip-service about being important: schools, public services, roads, unemployment benefits, etc.

It's also not hard to imagine a future filled with socio-economic and generational strife, as workers in their prime earning years have taxes skimmed off to pay for promises politicians made to pensioners years ago.