Updated: August 31, 2012

For active stock traders, how you navigate the intricate rules of the IRS can help to shelter your profits. If you’ve marked trading losses for the last year, the tax moves you make now will help limit your tax impact next year.

Here’s a quick rundown of everything you need to know.

Investors vs. Traders

The IRS tends to favor investors that buy and hold stocks for an extended period (at least one year). If you do, then you’ll be taxed at a very reasonable long-term capital gains rate of just 15%.

But stock traders have no such luck. These folks, who tend to hold on to stock for just days, weeks or a few months, are taxed at ordinary income tax rates. If you’re in a high tax bracket, that can really hurt. (On the other side of the spectrum, you don’t have to ai capital gains taxes at all if you are in the 10% or 15% tax bracket -- i.e., less than $34,500 in adjusted gross income for single filers.)

But whether your losses are short-term or long-term, you can only deduct up to $3,000 from sour investments in any given year. Any losses beyond that level can be saved for the next year, where they’ll again (hopefully) be used to offset your winners. I owned a few major dot-com duds back in 2000 that eventually went bankrupt, and I spent the next five years partially sheltering my gains.

With the recent extension of the Bush tax cuts set to expire at the end of 2012, it’s increasingly likely that tax rates for the wealthiest earners will go up in 2013. As a point of reference, the current top tax rate is 35% (for single filers with adjusted gross incomes above $379,151), and during the Clinton administration the top tax rate was 39.6%. With the higher investment taxes expected to be headed our way, you may want to start harvesting your winners before the end of next year.

Capital Gains and Losses

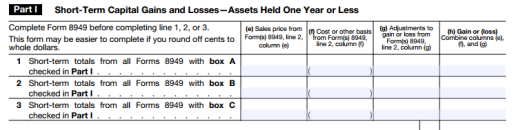

When you sell an investment, it is classified as either a capital gain or a capital loss, and all capital gains and losses must be reported to the IRS, using the Schedule D form. However, starting with the 2011 tax year, the IRS added another wrinkle. The IRS now requires you to also fill out a new form -- Form 8949 -- in addition to Schedule D, which now looks like this...

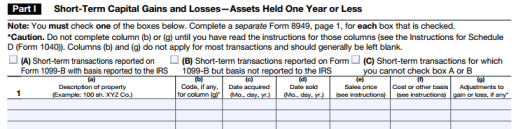

But before you get to Schedule D, you have to address Form 8949. That form gives you lots of room to list each of your investments from the year, then you just need to tally up the totals from Form 8949 and place them in the proper spots on Schedule D, and you're on your way. (For more information, check out 'Eight Facts About New IRS Form 8949 and Schedule D' at IRS.gov.)

If you took a few losses during the year, don't worry. You can use those capital losses to offset the money you made with your capital gains. Simply subtract the loss from the gain and you’ll only owe taxes on the difference. Someone with a $25,000 gain on a long-term investment and a $10,000 loss in a long-term holding will only have to pay taxes on $15,000.

Doing the Math

So how do you tally up a gain or a loss for a stock? On Form 8949, the IRS asks you to list…

- A description of the asset (name of the company, how many shares you sold)

- The date you acquired the asset

- The date you sold the asset

- The sales price (sales price x number of shares)

- What you initially paid for the asset (purchase price x number of shares)

- The capital gain or loss (sales price - purchase price)

This is when detailed recordkeeping becomes crucial. The IRS recommends keeping all forms you receive showing your investment income (e.g. Forms 1099-INT, Interest Income, and 1099-DIV, Dividends and Distributions).

Sometimes you’ll sell only some of that stock in the near term, and then sell the rest of it later on. I keep a spreadsheet that I update every time I buy or sell a stock. Keeping detailed records of your buy and sell prices will make it much easier to pull all of this together at tax time.

Time for a Wash

If you’ve been sitting on dud stocks from the stock market crash of 2008, but have an otherwise robust portfolio of winners, you may want to consider a “wash-sale” strategy.

Remember, though, there are certain constraints that surround this practice in order for it to be considered legal by the IRS. A wash sale occurs when an investor sells a security at a loss, then purchases the same or a substantially similar security within 30 days of the sale. The illegal part is when the investor claims the loss on his taxes as a deduction.

However, the IRS considers it a fresh investment if you wait 30 days before you buy that stock again. For example, if you sell 100 shares of XYZ Company for a $1,000 loss and plan to use this as a deduction on your taxes, you'll need to wait 30 days before you can buy that stock back again, or that of a similar company.

You’ll want to look at this strategy and put it in place well before the year is over; many investors wait until December only to realize it’s too late. (note that wash-sale rules apply even if you’re investing in options of an underlying stock.)

Taxable vs. Non-Taxable

Many investors aim to focus their investments in their retirement portfolios, which allow stocks to be bought and sold without triggering tax consequences in the near term. You should know that it’s best to stick with traditional stocks. Unusual investments such as Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) are not considered stocks, and the IRS discourages you from putting them in a retirement portfolio. It’s not illegal, but it may trigger another layer of paperwork with a Form 990 (which enables you to exempt income tax from the investment).

You’ll also need to determine what kind of dividends you have received in the current tax year. Most dividends are “qualified,” which means that they are taxed at the capital gains rate of 15%. But if you hold a stock for less than 60 days, or they are simply disbursements from a mutual fund’s capital gains or are part of the normal payout of a REIT or an MLP, then the IRS sees it as ordinary income and will make you pay the full tax-bracket rate on the gains.

Even though tax day comes a bit late this year -- April 16 -- there’s no need to wait, especially if you have a refund coming. And it’s never too early to start thinking about next year’s taxes -- the investment moves you make now can have a huge impact on the taxes you’ll face in 2012.

[InvestingAnswers Feature: A Simple Plan to Avoid Estate Taxes.]